Six years is a good run. It’s also an investment in fictional lives, a milieu, and the often unnamed things that matter. Botch the story, send the characters off into self-absorbed whining, or worse, bore your audience, and they quit watching. Keep viewers who watch until the end and then look at each other with an expression of, “I-wish-there-were-more,” and you have done well as a writer. Downton Abbey, I believed passed the ultimate test of literature – a presentation close enough to life without actually mirroring it so that it speaks to us. A private world is created and we are allowed to live in it. We learn. We take something with us after the experience. This blog is about that something.

Lesson one: More than money, social position, or even the possession of near absolute power that can raise up the lowly or cause the downfall of the unfortunate – Kindness rules. (Take that, you politicians today who practice various scorched earth policies.) Kindness is the ultimate currency that buys life and influence; it is the power that eventually beats all others. It is in a lady’s concern for the progress of a village hospital. It is in a lord’s concern for the quality of housing built on an estate to help fund the Abbey. It is in a daughter’s willingness to swallow her triumphant pride and call back her sister’s estranged lover because it is best for her sister. It is in the pat of the hand of a dowager who tells the lady who has taken over her position as president of the hospital that she is doing a wonderful job. Kindness marks the lives of servants who worry about each other, save their own from suicide, risk their own positions to testify in court, keep secrets or not depending on what they think is best for the other person. It marks the generosity of an earl’s American wife and later, a newly-married husband who put their entire fortunes at the disposal of the family and the estate.

The greatest kindness is the vein that opens even in the prick of meanness. Because of it, the dog-stealer, the rebel, the scandalous, war’s wounded, and the petty autocrats are redeemed. Kindness heals; it makes the broken whole; it makes the savage human and the unsophisticated better than the aristocrat. When in doubt – be kind – always. At this point I am led to a greater passage – Portia’s speech on mercy from The Merchant of Venice, which many of us had to memorize (with good reading). “The quality of mercy is not strained. It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven on the place beneath. It is twice blessed. It blesseth him that gives and him that takes….” Part of the lesson from Downton Abbey is that when the people are not kind, things do not go well, not for their rivals or themselves. The story of the under-butler Barrows is the best illustration. He almost died because of his own meanness and was saved only by the last-moment concern of a lady’s maid.

Lesson two: Nothing lasts. One would think that a house, an estate, a title chiseled into a culture and layers of traditions over many generations would ensure the continuance of those things, but it is not so. One of the interesting things is that Americans, we title-less, disorganized, anything-goes Colonials could be so fascinated by a class system we do not want, barely understand, and would certainly resent if it were imposed in the States. After all, we’ve developed our own class system based on money, which anyone can join if he or she has enough, no matter how that wealth was amassed. The Kennedys, the Rockefellers, the Gettys, and even the Walton family come to mind. What many did to get their fortunes may or may not have been legal; much certainly was unethical, but they did not get caught, or if caught, they found an oily way out. Fortunes are lost, not always by blunders, theft, or revolution. A fortune is lost because it is almost inevitable. It may take several generations, but it may also happen because a comma, a minuscule serif, is inserted in a piece of otherwise well-meaning legislation. Big Oil is a recent example, but there are others. Do you still own Sears stock? Enron? Bell Telephone? American Motors? Zenith Electronics? Even those that still exist are poor step-children today, sometimes the scullery maids who must get up first to clean out ashes and stoke the fires for others. Some ruined their own prospects; some fell to changing economic conditions, and some were simply swallowed up by predators.

Even love may not last. It is interrupted by death, trouble, self-centeredness, pride, and faithless behavior. Love is a choice, and it must be re-chosen every day. We must tell our spouses. I choose you. I choose you. I choose you. Someone else may temporarily seem to be a better deal, but I choose you for the long term. Counselors tell us marriage is killed by disdain and the repeated eye roll. That means it is important we tell each other as often as possible: I choose you again. Designing maids may seduce lords. Ladies may be overly-appreciated by art historians. A visiting Turkish diplomat may die in a lady’s room. A chauffeur may marry a titled lady. We choose, and when we choose for the long term, things almost last. At least they last for long enough. At least they may last for a lifetime. What more could we ask?

Lesson three: No matter what our position, power, or personal integrity – we all just muddle though. In one of the most prescient titles of all time, Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart reminds us all that Plan A is never enough. As Bobby Burns put it, “The best-laid schemes of mice an’ men gang aft a-gley.” In Downton Abbey we see the repeated near-bankruptcy of a privileged estate, a witness to other estates that failed, decayed, and became the mere ornament for the ultra-materialistic nouveaux-riches. Even the terms used to describe them are hyphenated.

In Downton Abbey, ovens break down the night of an extended family banquet; an old letter tossed into a fire nearly burns down the house; the joyful birth of a son is overshadowed by the death of the husband in a car crash, the same kind of accident that eventually sends Mary another husband. A child is born before Edith’s true love can marry her. An outsider, even worse, an Irish activist and mere chauffeur becomes the common-sense savior of the family estate. A bright, but naive daughter inherits a publishing company. A mere footman becomes an admired teacher who knows more than many graduates of Cambridge. All of this muddling, like struggles in any life, may seem impossible, but the older one gets, the more one has seen the impossible. A poor, black boy with an absent father becomes president. The presumptuously-named God-particle is found. A tiny wave in the time-space continuum is detected. Cancer cells may be “tagged” so one’s own immune system sees them as invaders and attack. Curiouser and curiouser. No one stays clean all the time. We rust. We sag. Our eyesight fades. Our memory gets more selective. It’s true of me, of you, of the famous, of the powerful, of the simple, of professors, of mothers who would give almost anything for a full night’s sleep, of fathers who don’t know where the next job will be, or the father who would give almost anything for a full night’s sleep, or the mother who doesn’t know where the next job will be. It’s all the same. We muddle through. We Muggle through. Magic may happen, but we have no wands.

The muddling makes us grow, and if it does not kill us, it makes us stronger. That is how LadyMary learns to run an estate; Lady Edith learns to edit a magazine; Molesley learns how to be a teacher, and Robert learns how to let go, possibly the most difficult lesson of all

Lesson four: No one succeeds alone. It was fascinating to watch the Abbey work on a daily basis like a finely-calibrated watch. Not always, but usually. The clearly defined roles and coordination were amazing. Even more powerful was the handling of a crisis. A dead body was moved. Farms were run; sick pigs nursed; fires put out; deaths mourned; banquets prepared. It was done by people thrown together by circumstance, by choice, and sometimes by necessity. Even when some said, “No,” others stepped forward to offer support. If you want to help, but there is really nothing you can do, give empathy. Empathy heals as well or better than kindness and often better than misguided intention. The fast friendship of Lady Violet and Matthew’s mother Isobel Crawley was not cemented by kindred spirit or even similar interests. It was firmed and confirmed by empathy. Sometimes they merely sat with each other, listened, and “felt.”

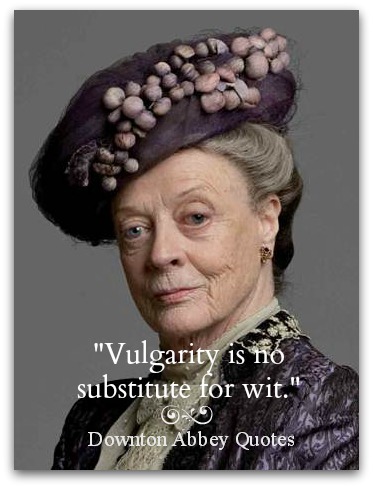

Lesson 5: Wit is always fun. My favorite character had to be Violet. At least she had the best lines, including several classics. “Weekend? What is a weekend?” About her friend Isobel in a tussle over the hospital. “Fight? Of course she’s allowed to fight. She’s just not allowed to win.” Even in her backhanded slaps, the harm is not so great from one somewhat physically feeble, someone still mentally sharp, and someone wearing a velvet glove. Comic relief is always important. I tried very hard to put it in my book, Hibernal, in the scenes with Porkchop andTrailer. It seems that some readers remember only that about the book. If they laughed out loud, as many readers reported, I am satisfied.

All good things must end. Years ago I wrote a blog making fun of Downton Abbey, its excess, its confusing multiplicity of characters and emotional highs and lows. Somewhere along the line, I was won over, quite possibly because the reasonableness of its excesses, its interesting multiplicity of characters, and its emotional highs and lows. My disbelief certainly was suspended. If you win over a skeptic like me, you’ve done something, Julian Fellowes.